4gg

THE STORY OF ENDOSULFAN POISONING IN KERALA

h

kkj

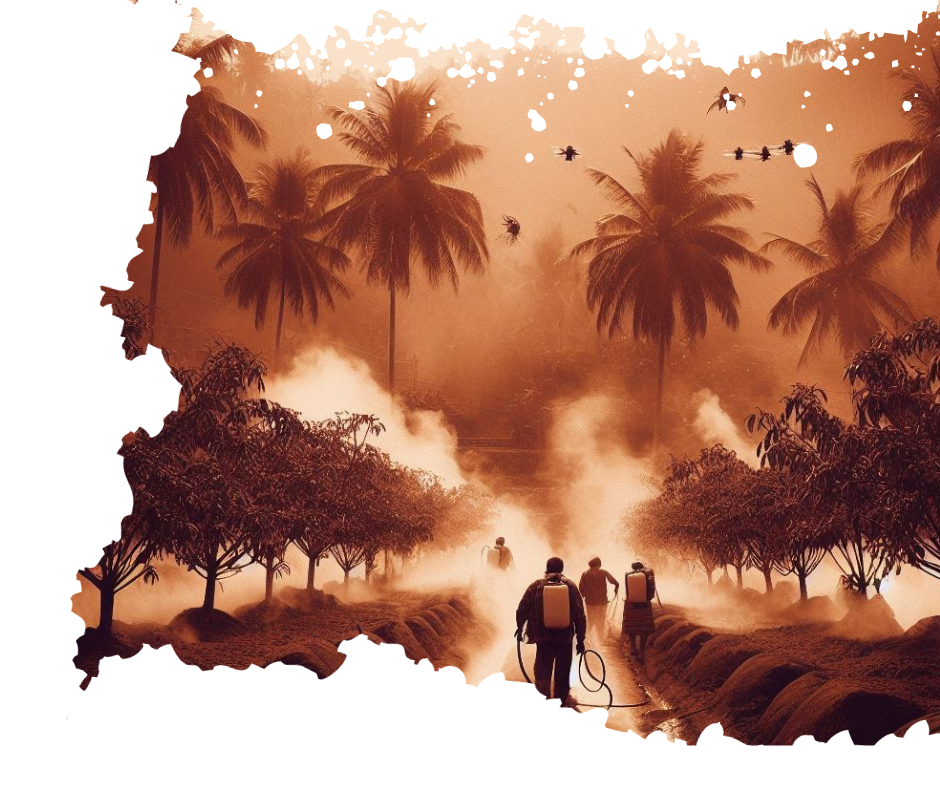

Around 1963-64 the agriculture department started planting cashew trees on the hills surrounding Padre. In 1978, PCK took control of the plantations. Insecticides were first used to control the tea mosquito, which is a major pest that affects yields. The first insecticide used was endrin. Later, PCK started using endosulfan. It was first sprayed by aerial spraying around 1976. On December 25, 1981, the Evidence Weekly magazine published an article titled “Cows Giving Birth to Calves With Deformed Limbs After Aerial Sprays of Endosulfan”. The author of the report is a farmer and journalist named Shree Padre, who is passionate about agriculture, environment and matters of public interest.

In the Kasargod district of Kerala, the villages close to cashew plantations have been ravaged by an unusually high number of cancer deaths, neurological issues, and various kinds of mental and physical impairments. Reports in the media and studies done in the area suggest a strong connection between the spraying of Endosulfan pesticide and the poor health of the locals. Unfortunately, the State administration seems to be ignoring the issue. People turned to courts for help. The PCK has been spraying endosulfan which has been banned in many countries. Various media reports and studies conducted by institutions such as the Centre for the Science and Environment in New Delhi have shown a strong correlation between endosulfan aerial spraying and the number of deaths and diseases in the area. The Government of Kerala and the Central Government have not responded very late in this tragedy.

So many organizations and several local committees came forward against Endosulfan. In the meantime, a team of CSE scientists visited Kasargod at the end of February and collected samples from the village of Padre. The scientists were assisted by Dr Sripati Kajampady. The scientists drew and tested a large number of samples at CSE’s Pollution Monitoring Laboratory. The results of the tests were shocking. The researchers found “alarming” levels of residue in the blood and tissues of Padre villagers, as well as in water, milk and soil samples, as well as fruit and vegetables. The report concluded that “it is beyond reasonable doubt” that the dramatic events in Padre village of Kasargod, Kerala, can be directly attributed to the decision-making process of a government undertaking that has used aerial spraying of Endosulfan three times a year since 1976 without adequate consultation or debate with experts in other fields such as pesticides, social sciences, environmentalists and others.

Thanal, Thiruvannanthapuram-based Environmental NGO, which has conducted extensive research on organic pollutants and conducted a study on the effects of Endosulfan on Kasargod society, stated that Endosulfan is classified as a Pesticide with a restricted use. The chemical has been found to be endocrine disruptive and genotoxic, with the central nervous, kidneys, skin, and reproductive organs being the primary target organs. According to the Thanal report, accidental ingestion and inhalation of high concentrations of the chemical can lead to convulsions and even death. The Thanal report mentioned that whether the threat posed by tea tree mosquitoes and other fungi found on cashew plantations on a regular basis is sufficient justification for spraying a pesticide that threatens public health. C. Jayakumar, Executive Director of Thanal, points out that since the PCK has accepted organic management practices among farmers, and there is no reason why it cannot adopt these methods for the production of cashews.

At this time, the public outcry against the aerial spraying of Endosulfan was intensifying. In February, 2001, the Munsif court of Kasargod issued a stay order on the endosulfan application in Kasargod. Some agricultural scientists, including the Director of the National Research Center for cashew, strongly criticized the CSE report, claiming severe shortcomings in the study, to which the CSE responded at a later date. The Kerala Agricultural University’s (KAU) team conducted its own study soon after the CSE’s report, which showed no residues of the active metabolite in water samples, pepper berries and betel leaf samples, but high levels of the metabolite in soil samples and cashew leaf samples from within the plantation. The PCK sponsored their own study, which was conducted two months later, and showed only small amounts of the metabolite present in cashew leaves and soil samples, but no residues in water, human blood, fish and milk samples.

The government of Kerala then set up a committee under the chairmanship of Dr.Achyuthan to investigate the problem and make recommendations for remedial action. The report of the committee was issued in November 2001 and included the following recommendations:

- Ban aerial spraying in cashew plantations of PCK of Kasargod district.

- Freeze the use of Endosulfan for 5 years.

- A thorough investigation should be carried out by scientists from all related fields to determine the risk factors behind the high mortality rate in Padre village, and other areas.

- The health survey should include plantation workers.

- The right to information regarding pesticides should be respected.

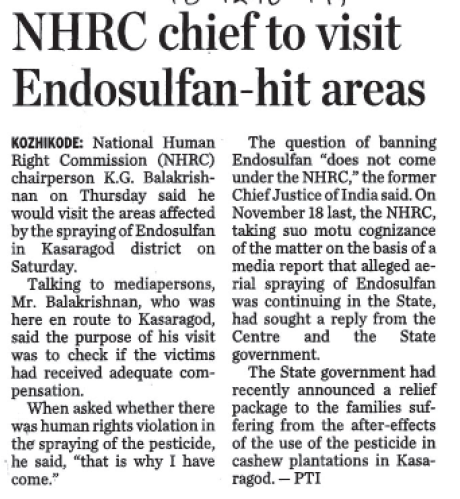

In August 2001, The Government of Kerala ordered that the insecticide Endosulfan should not be used in crops/plantations in Kerala until further orders. The High court of Kerala banned endosulfan in Kerala in 2003. The Central Government withheld the sale and use in Kerala in 2005. Several local protests broke out in Kasaragod district demanding ban of endosulfan. This paved the way for bringing the issue to the state and national level. Later it has even reached international forums such as the Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) Review Committee of Stockholm Convention, which resulted in a global ban of endosulfan in 2011. The same year Honorable Supreme Court of India ordered a national ban on this toxic chemical. Meanwhile, the national human rights commission has ordered to pay compensation to the individuals who were harmed by endosulfan poisoning.

In 2001 the NHRC initiated suo moto action on the report entitled “Spray of Misery” published in India Today (July, 23 2001) and asked a number of agencies including ICMR to submit a report within four weeks. On the directives of the Director General ICMR, a three-member team from NIOH visited the affected areas and collected first hand information and a preliminary report was submitted to the NHRC.

The Commission on December 31, 2010, through a detailed order, had recommended that the State should pay at least Rs 5 lakhs to the next of kin of those who died and to those who were fully bed ridden/unable to move without assistance or mentally retarded and Rs 3 three lakhs to those who have got other disability. The Commission has also observed that the Government of Kerala is bound to compensate and rehabilitate the victims. The State Government vide order dated 26th May, 2012 had notified that the recommendations of the NHRC were to be implemented and also laid down the method by which the compensation was to be paid to various categories of victims of endosulfan